|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

Pawel Althamer & Artur Żmijewski James Lee Byars Sophie Calle & Fabio Balducci Center for Tactical Magic Peter Coffin Jennifer Cohen Anne Collier Christian Cummings Trisha Donnelly Douglas Gordon Brion Gysin Friedrich Jürgenson Joachim Koester Jim Lambie Miranda Lichtenstein Euan Macdonald Jonathan Monk Senga Nengudi Paul Pfeiffer Eva Rothschild Mungo Thomson All Artists |

|

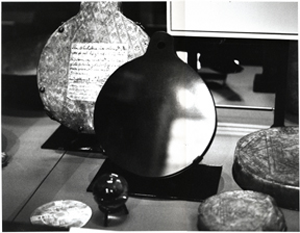

Joachim Koester Magical Mirror of John Dee, 2006 Black and white print |

|

|

|

JOACHIM KOESTER (b. 1962, Copenhagen, Denmark) has solo exhibitions this year at Paris’s Palais de Tokyo; the Centre d’Art Santa Mònica in Barcelona, Spain; and Lunds Konsthall in Sweden. Koester recently exhibited Sandra of the Tuliphouse or How to Live in a Free State (with Matthew Buckingham, a frequent collaborator) at The Kitchen, NY (2005). At last year’s Venice Biennale, his work was featured in the Danish pavilion. Both a photographer and filmmaker, Koester lives and works in Copenhagen and New York. The Magic Mirror of John Dee There is a way of seeing that does not rely on the eyes. It emerges in the state between wakefulness and dream, when patterns and shapes flash behind the eyelids, or as trance-induced visions, while gazing into a crystal ball or at a black mirror. John Dee (1527–1608), scientist, astrologer and owner of the biggest book collection in England, did not possess this ‘second sight,’ but hired necromancer Edward Kelley—earless after a conviction for forgery—as his medium. Together, over a period of seven years, they conducted a number of magical séances, which became known as The Enochian Works. Enveloped in trance, Kelley would stare into a crystal ball or a black glass, apprehending images and messages from the otherworld. At his side, Dee would transcribe the events with utmost precision. Slowly, through these ‘works’, a new language called Enochian materialized. A magical system of evocations and a mapping of a mental landscape with numerous celestial cities inhabited by angels, and, further out, beyond four watchtowers, swarms of demons. It was one of these gates of the mind that Aleister Crowley—who believed he was the reincarnation of Kelley—opened ajar with the help of poet Victor Neuburg in the North African dessert near the village of Bou Saada in 1909. By means of an Enochian ritual that lasted for days, Crowley conjured Choronzon (better known as the death-dragon). The demon rose from the abyss of meaningless forms to momentarily posses Crowley and terrify Neuburg, who had to fight off the attacking Crowley (or Choronzon) with a magical dagger. Neither Dee nor Kelley was unambiguously successful in their magic ventures. While Uriel, Madimi and the other angels they summoned were more friendly and cooperative than the demon Choronzon, Dee’s notes can read as a list of disappointments. The angels made promises and—even more so—demands, but no matter what actions Dee and Kelley took to accommodate their shifting moods, uncertainty prevailed. Words in the otherwise ‘perfect’ language of Enochian were never disclosed and following the advice of the angels led to random or at least surprising results. Dee ended his life isolated and poor, while Kelley fell to his death during an attempt to escape imprisonment. Today the lengthy manuscripts that make up The Enochian Works can be found at The British Library. The crystal ball and the black mirror used in the séances are exhibited in a showcase in The British Museum. Here, the imperial architecture of the museum is reflected in miniature by the crystal ball, while the visitor’s gaze is greeted by a dark absence when it encounters the mirror. A blank surface that although mute, seems to emanate a narrative persistence, a sleeping presence, not unlike a photograph. |

||||||

|

|

||||||